Top 15 reasons that make Molise the new coolest region to visit in Italy

After Basilicata (Maratea, Matera, Craco), we planned a road trip to another even more uncharted territory of continental Italy: the Molise region.

There is a reason why Molise is off-the-tourist-radar: it is one of Italy’s most discrete and geographically most unusual regions. It became an independent region only in 1963, after being part of the Abruzzi e Molise region. It is also the second smallest region of Italy with no airport, only 40 km of motorway along the coast and two major roads flowing from the coast inwards.

Molise is a mountainous region with a wealth of little gems scattered all over the territory, often in the most unexpected places or hidden in nearly inaccessible mountain villages, at the end of scenic, but challenging roads. All of this, of course, makes it a paradise for travelers wishing to explore Italy on an offbeat road trip.

After a 1,000 km road trip in a sanctuary of peace and silent poetry, a land of unspoiled nature, stunningly diverse landscapes, amazing history and traditions, delicious local wine and food, and of a hospitable, noble and independent people, here are at least 15 reasons that make us say that Molise is the new coolest region to visit in Italy.

1. Treasure trove of secret places and hidden gems

Traveling in Molise is really akin to going on a treasure hunt. The myriad of secret spots and little gems in the most unusual places is what characterizes this region: like this marvelous crypt with frescoes dating from the 14th century Sienese school in a small, modest village, Sant Angelo in grotte, or that ancient Roman Mausoleum dedicated to a VIP of the 1st century AD in the middle of a sheep trail, next to a working farm in Altilia, or this impressive theater built in the 2nd century BC outside a village with less than 850 inhabitants, Pietrabbondante, or that abbey San Vincenzo al Volturno, dating from the 7th century that was completely dismantled and carried across the river to be reconstructed on the other bank of the river…seemingly in the middle of nowhere.

Be prepared to re-route and re-schedule your day trips a lot, as this is the land where is does not rain cats and dogs, but where secret and unexpected little treasures keep popping on the road.

2. An incredible maze of beautiful, interesting mountain roads for an off-beat road trip

The network of major roads is scarce, with only one motorway (along the coast) and two highways flowing from the coast inward, but that is also precisely the reason why the territory is so well preserved.

Instead, the region is relatively well interconnected thanks to a maze of smaller back roads and asphalted rural roads. However, don’t expect these smaller, local roads to be smooth like billiard tables all the way. As 78,7% of the territory is mountainous, a lot of these roads end up being winding mountain roads, including with the occasional dips, potholes, and traces of landslides.

This be said, it are precisely these smaller roads that are often the most interesting ones, when not THE only access to a village of interest.

It suffices to open a road map where scenic roads are high-lighted (in green, for example, on Michelin road maps) to note that the concentration of scenic roads is exceptionally high as compared to the surface of the territory and that many of them are of the local type (B and C roads, in yellow and white on maps, respectively).

So, this is definitely a region that is best explored the old school way with a good paper road map and asking directions, rather than relying exclusively on a GPS. Most of the time the GPS will probably not indicate the most interesting locations or backroads of the region anyway.

3. Remote little villages that look like they come straight out of a story-book

Apart from the two province capitals, Isernia and Campobasso, the beautiful seaside town of Termoli and a few smaller, but historically important towns (see: Agnone), most of Molise’s population lives in relatively remote mountain villages. Out of the 136 comunes of the regoin, 111 are real mountain villages and another 12 are partially mountainous.

Many settlements in Molise were not built in the valleys or on the mountain slopes, but on the very top of the mountains, which creates a very unique and surprising landscape. It is relatively rare to see isolated single residences; houses are usually grouped in small clusters or hamlets, leaving the rest of the territory often completely uninhabited.

Most of these villages are so atmospheric that we could easily imagine a famous fiction author plotting a novel here.

4. Amazing viaducts and castles

After a while on the road, one gets the impression that Molise must be the Italian region with the highest ratio of viaducts per square km. Some of these viaducts are true works of engineering art, as they seem to have been built with the utmost care as to not disfigure the natural landscape, instead of taking the straightest and most low-cost solution tracing through hills and villages, as is unfortunately too often the case.

A perfect example is the viaduct over Lake Guardialfiera that was traced around Monte Peloso, which creates both a unique view and unusual sensation when driving over the water.

The small region also has a considerable number of castles dating from the Lombard, Norman and Angevin ages, among which the Castle of Venafro, the Angevin Castle of Civitacampomarano, the Montforte Castle of Campobasso, the Castle of Tufara, the Castle of Pescolanciano, the Castle of Roccamondalfia, the Gambatesa Castle and, of course, the Svevo Castle of Termoli and the Castle of Campobasso, just to name a few.

5. Villages wrapped around rock pinnacles that defy every law of physics

The center of Molise is characterized by a collection of impressive sedimentary rocks, locally known as Morge, of which the oldest ones are of marine origin. A park known as the Parco delle Morge cenozoiche del Molise has been established to celebrate this unique natural phenomenon.

The name of the park derives from the fact that the rocks came into existence about 66 million years ago, at the beginning of the Cenozoic Era when the Earth’s continents moved into their current positions. The ten villages that are part of the park offer possibilities for trekking, hiking, biking, and climbing.

At about 5km of Pietracupa there is also the Morgia of Pietravalle, with hints of ancient rock dwellings. Legend has it that it was used as a shelter for brigands, reason why it came to be known as Morgia dei Briganti.

6. Relatively uncharted territory for amazing street and Urbex photography

The relative remoteness of about 70% of the region and the variety of subject matters make Molise a perfect playground for creative photographers with a passion for exploring uncharted territory.

The region’s urban and scenic silent beauty is immensely inspirational. In many a village ruins coexist with residential buildings, creating an eerie atmosphere of semi-ghost towns and desolate panoramas, combined with the colorful vegetation and overcast skies, making this region a compelling destination both from a traveler’s and photographer’s perspective.

There is an abundance of amazing street art everywhere, both intentionally and unintentionally created, either performed by national and international artists or… by the effect of time.

The kind of unintended aesthetics that is full of poetry and can be furiously inspiring …or pushes oneself to introspection.

The ghostly beauty of abandoned and decaying buildings are part of the landscape. The kind of unintended aesthetics that is full of poetry and pushes oneself to introspection.

7. Trabucchi and tratturi, fading symbols of traditional fishermen’s and farmers’ culture

There are few regions where one can still immerse oneself in tangible traces of the traditional fishermen’s and farmers’ world : the trabucchi along the coast and the tratturi across the territory. They are like snapshots of a world suspended in time described by the Italian poet and writer Gabriele d’Annunzio in Il Trionfo della Morte and I pastori as “silent verdant rivers” and “strange fishing machines that looks like a giant spiders, made of boards and beams, respectively”.

The trabucchi are ancient fishing machines typically seen on the lower Adriatic going from the coast of Abruzzo to the coast of Gargano in Puglia. However, the type of Trabucco found in Molise is different from those found in Puglia. In Molise, they are usually smaller, with less antennae (the long arms to which the nets are attached) and built on a platform above the sea, instead of anchored on rocks as in Puglia. Trabucco are used for sight fishing to intercept schools of fish as they move along the shore.

They were a way to guarantee a decent catch of fish even when the fishing boats could not sail out due to bad weather.

The tratturi are the natural transhumance trails followed by pastoral farmers during this seasonal rotation of herding between fixed summer and winter pastures. Traditionally, Molise was the region through which flocks coming from the cool mountain pastures in Abruzzo passed to go the warmer Puglia Tableland in Autumn, and vice versa in Spring, in order to cope with seasonal fluctuations in heat, water and fodder.

The farmers practicing transhumance had their own customs, cuisine and handicraft related to this particular way of life. The marks of this heritage are still visible not only in the cuisine, but also in the folklore, economy and, of course, territory itself.

Twelve tratturi cross the Molise region, covering a distance of about 1500km from North to South and from the Adriatic coast to the foot of the Matese mountains, among which the most important are: Pescasseroli-Candela (211 km, see further), Aquila-Foggia (Tratturo del re, 243 km), passing by Termoli, Celano-Foggia (207 km), which crosses the Archaeological areas of Pietrabbondante and Vastogirardi, and Castel di Sangro-Lucera (127 km) with the Castle of Pescolanciano.

These routes of transhumance form a rich parallel network of green roads for hikers and riders who wish to explore the territory following natural itineraries and immerse themselves in an environment that has remained largely unaltered while at the same time crossing archaeological sites, monuments and towns of historical interest.

8. Impressive archaeological sites related to one of the fiercest opponents of Ancient Rome

The original people of Molise, who called themselves Safineis, but were elsewhere known by the name Samnites, were a fierce and independent people who where in constant opposition with ancient Rome. They had their own language and alphabet (see our article about Agnone and the Tabula Agnonensis), and their own social and political norms with great emphasis on human rights and family matters.

Their political organization was based on a democratic and meritocratic system of semi-independent districts (the Pagus), as opposed to the system of city-state of the Romans, strongly influenced by the wealthy patrician families. It was precisely to defend these values that the Samnites grew into fierce warriors ready to defend their culture against invaders. It took the Romans three savage wars between 343 and 290 BC to conquer the the Samnite territory.

Today’s territory corresponds more or less to the ancient territory of the Samnites, while the region takes its name from a small fortified medieval Duchy near Campobasso.

The tratturi, described in the previous point, are an interesting way to describe the Samnite culture as it were the Samnites who first organized and controlled this network of roads formed by these sheep trails. It will therefore come as no surprise that many of the Samnite settlements and later Roman colonies lie precisely on the original tratturi.

On the Pescasseroli-Candela tratturo one finds Aesernia (Isernia), Saepinum (Altilia, near the current Sepino) and Bovianom (present Bojano, not to be confused with Bovianum Vetus, the location and very existence of which is still a matter of dispute) and Castelpetroso.

The Samnite temple-theatre of Pietrabbondante (Calcatello), dating from the end of the 2nd – beginning of the 1st century BC is part of the Celano-Foggia Tratturo. The theater, which served both for performances and as a sacred place dedicated to administrative duties, is an important testimony of the Samnite culture. Excavations have brought several shops and accommodation quarters to light showing that at the time of its construction the temple had a more central position. Weapons unearthed on the site have also shown that it was the scene of numerous battles.

Worth visiting is also the Museo dei Sanniti (Samnitic Provincial Museum) in Campobasso, and the archaeological site of Larino, territory of the Frentani, who where closely related to the Samnites.

9. Fascinating century-old craftsmanship

Being a region with a huge sense of territory and family, it is not surprising that Molise can still pride itself of a wide variety of ancient traditional crafts and is also home to the oldest continuously family-owned and run manufacturing company in the world, the Fonderia Marinelli (bell foundry), founded more than 1000 years ago.

Molise is also renowned for its tradition of hand-made, folding knives. There are historically three centers of knife making in Italy Maniago (in Friuli-Venezia Giulia), Scarperia (in Tuscany) and Frosolone in Molise. Typical of Molise are the folding, pocket knives, a relic of the rural habit of always carrying a working knife in one’s pocket. However, when knives became more and more involved in street fights and duels, two restrictive laws were passed in Italy in 1871 and 1908, which prohibited pocket knives with fixed springs and blades longer than 4cm (1.57 inches), respectively.

This led to the development of new types of knives, such as the Sfilato a punta tonda, Zuava with turtle-like (tartarugato) handle and Mozzetta, which are typical of Frosolone. As the tip of the Mozzetta’s blade was cut off it was not subject to the legal limit of a 4cm for pointed blades, which immediately made this type of knife very popular.

We were lucky enough to visit the workshop of the fifth-generation knifemaker of Frosolone Rocco Petrunti and see the “birth” of a hand-made knife unfold in front of us from beginning to end. The accuracy and precision of each step to form the blade and the handle until the delicate finishing touches is really incredible!

Apart from the bells from Agnone and knives from Frosolone there are also the traditional bagpipes (a typical instrument used by shepherds) of Scapoli, the pottery of Guardiaregia, and the very refined art of bobbin lace of Isernia.

10. All types of climates and geographical features within a range of 100km

Considering that Molise is the second smallest region (after Val d’Aoste) it is surprisingly diverse in terms of geographical features and climatic variations. The region has no distinctive climate, but rather displays the entire array of different climates seen in Italy, from the harsh winter temperatures and heavy snow fall in Northern Molise, to the mild temperatures along the coastal strip.

This explains how it is possible to find oneself under an alpine-like snow storm in Pietrabbondante and enjoy the mild climate of a seaside resort all within the same afternoon. Skiing and riding on the slopes of Campitello Matese, then having a coffee on the sunny terrace where its 15° C hotter within the same day, it’s all possible in Molise.

11. National parks and wildlife sanctuaries

The small region of Molise is blessed with great biodiversity due to its variety of climates and ecosystems ranging from its high mountains and hills, to its rivers, coast, gorges and three lakes, and its woodlands and shrublands that cover 35% of the territory. As the impact of human activity has been limited the natural environment has remained largely untouched.

In autumn, the different species of trees, shrubs and evergreens offer a unique scenery of colorful patterns. The local fauna includes Roe deers, fallow deers, lynx, otters, foxes, badgers, hedgehogs, bats, marsican brown bears, various species of sedentary and migratory birds, including birds of prey.

Several environmental associations and international agencies have taken an interest in the region’s environmental heritage leading to the creation of a great number of natural reserves and wildlife sanctuaries, protected for their environmental value and rich fauna and flora.

Among these are the Collemeluccio-Montedimezzo MAB Reserve, one of only 245 reserves set up by the UNESCO around the world, the Guardiaregia-Campochiaro Natural Reserve established by the WWF with its falls, gorges, torrents and 33 species of wild, the Lipu Natural Reserve near Casacalenda with 400 different species of butterflies and various other species of animals.

There are also two parks of both environmental and archaeological interest, the naturalistic-archae0logical Park of Mount Vairano (2000 hectares) where the remains of a Samnite city have been discovered (possibly ancient Aquilonia) and the Parco regionale dell’Olivo di Venafro (550 hectares)

Last, but not least there is also of course the National Park of Abruzzo, Lazio and Molise.

12. World-class and one-of-its-kind war museum

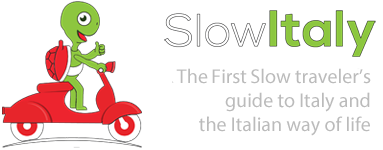

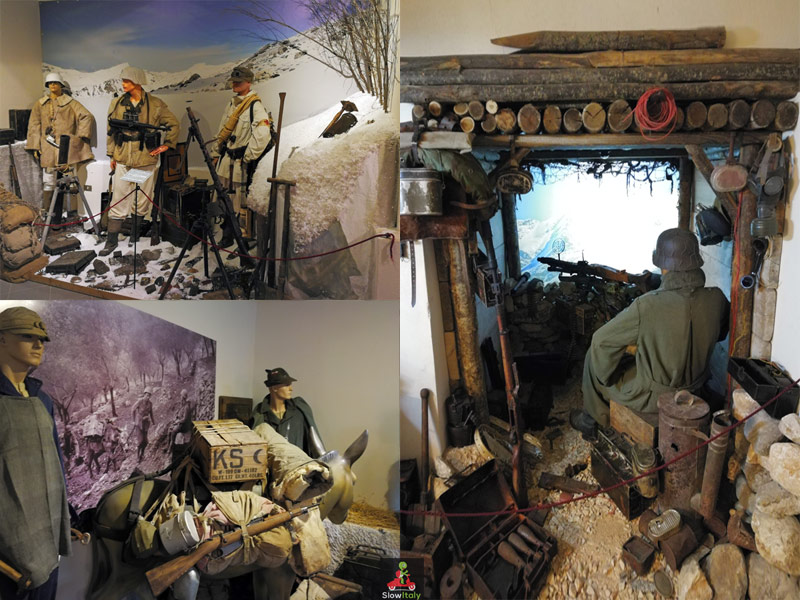

One of the astonishing discoveries during our trip in Molise was the world-class Winterline museum of Venafro. Although totally unadvertised by the city and housed in a relatively small space as compared to the wealth of artifacts it has on display, this museum is a true gem that will satisfy even the most seasoned WW2 specialists. Actually, even visitors who are, on principle, not interested in the topic will be impressed not only by the museum itself, but also by the passionate commitment with which it was put together.

Ineed, the museum’s rich and surprising collection of battlefield artifacts, equipment and memorabilia is so impressive that it is hard to believe that it has all been collected locally, year after year, by the curators themselves, on the arid mountains surrounding the little town. The same mountains that were the scene of one of the harshest and most tragic events of World War II, the crossing of the German defensive line called Bernhardt Line (or Reinhard Line) by the allied troops during the Winter of 1943 (hence the name Winterline).

Bottom: 6th Regiment of Moroccan Sharpshooters and 4th Moroccan Mountain Division, on the French front, in front of the village of Viticus. Photo by Jacques Belin, february 1944

The various objects (including some very rare First Special Force’s equipment and the most surprising daily life items) have been arranged in a sequence of lively and didactic dioramas, complemented with photos, war art and infographics, that help the visitor to understand what the soldiers on all sides (German, American, Italian, British and French, including auxiliary units of Moroccan Tabors) experienced. The accuracy and precision with which the events have been researched and transcribed is really extraordinary, as is the passion and poise with which the four boyhood friends decided to share it with the rest of the world and give veterans and relatives of soldiers the possibility to reconnect with an important part of their history.

The entrance to the museum is free and subsistence of the museum relies partly on donations by visitors. We were lucky to receive a very informative private tour of the museum by Luciano Bucci and Domenico Vecchiarino. Visits can be arranged by phone or email.

13. Unique folklore and spectacular traditional festivals

There are not only the verdant silent rivers of the tratturi, but also the rivers of fire of the ‘Ndocciata, an ancient festival celebrated in the town of Agnone. The ‘Ndocciata consists of an impressive torchlight parade of a large number of hand-fan-shaped, wooden ‘ndocce (torches), carried by men dressed in traditional costumes on the day of the Immaculate Conception, December 8 and on Christmas Eve.

Molise counts numerous magnificent festivals, feasts and popular events based on its farming tradition, seasonal food and sacred events, such as the ritual ox-cart parades (carrese) of Larino, Ururi, Portocannone and San Martino in Pensilis in May, the one of Larino being the most ancient manifestation of Molise.

Tradition has it that the Larino Carrese Festival dates back to 842, when the inhabitants of Larino took possession of the relics of St Pardus, kept in Lucera, in the province of Foggia, reason way this wonderful tradition is dedicated to the Saint. However, each comune has it’s own festival with its own peculiarity and history that makes it unique.

Then there is also the Jelsi Wheat Festival, celebrated on July 26 with a procession of the traglie, antique carts without wheels, the procession of the Misteri in Campobasso on the Sunday of the Feast of Corpus Christi, and the Festival delle birre artigianali Molisane (beginning of August).

Worthy of mention is also the Gl’ Cierv – L’Uomo Cervo (deer man) in Castelnuovo al Volturno, a pantomimic performance that combines magical religious rituals and hunting scenes, with as protagonists the deer, the ram and the hunter, celebrated on the last Sunday of Carnival. The origin and meaning of this very ancient festival remain clouded in mystery.

14. Delicious food and wine

From Venafro that was famous for its olive oil already cited in the De Re Rustica written in the middle of the first century AD, to its black and white truffles, over a great variety of cheeses, refined fresh pasta recipes, and delicious traditional dishes, the food of Molise is an experience in itself.

Since Antiquity, Molise has been a land of exchanges, being a territory of passage on the conquest and transhumance routes. Its resulting cuisine includes a wide variety of traditional dishes stemming from the cucina povera of the farming culture and transhumance, to the typical fish-based dishes of the coast, occasionally sprinkled with influences from the peoples that had settled on its territory in the mean-time.

Molise’s local wine, Tintilia, is a little gem, which comes as “reserva” or wine for immediate consumption.

15. Hospitality and availability of the people

Saying that Molisians are hospitable and affable is an understatement. Rarely have I encountered people as eager to share information about their territory and their culture, while at the same time being very discrete and unintrusive. As long as you don’t seek interaction, you will enjoy the feeling of having the territory all to yourself, but if you are in need, locals will walk more than the proverbial extra mile to show you around or help you out.

These fifteen points are by no means meant to be exhaustive. It is in fact nearly impossible to summarize such a fascinating and intriguing territory in a few points. Even after having traveled hundreds of kilometers Molise leaves the impression that there is still a lot left to be discovered and made us leave with the promise to ourselves that we will be back soon!

Photo credits: all photos © Slow Italy, except Castle of Pescolanciano by Pietro Valocchi; knives by Rocco Petrunti; Festival della Zampogna © cenz07; Parco Nazionale Abruzzo Molise by Lorenzo Assentato; ‘Ndocciata by Gianfranco Vitolo; Gl’ Cierv © Vincenzo Desiderio;