Agnone, home to the world’s oldest family-owned manufacturing company

Agnone is a pretty hill-top town at 840 m height, overlooking the verdant Verrino valley in the Molise region of Southern Italy. Dubbed the “Athens of Samnium” due to its archaeological and cultural heritage, it is located at about 20km of the Samnite theater-temple complex of Pietrabbondante.

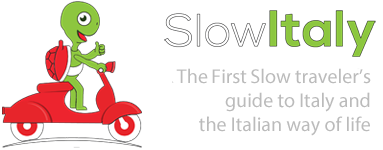

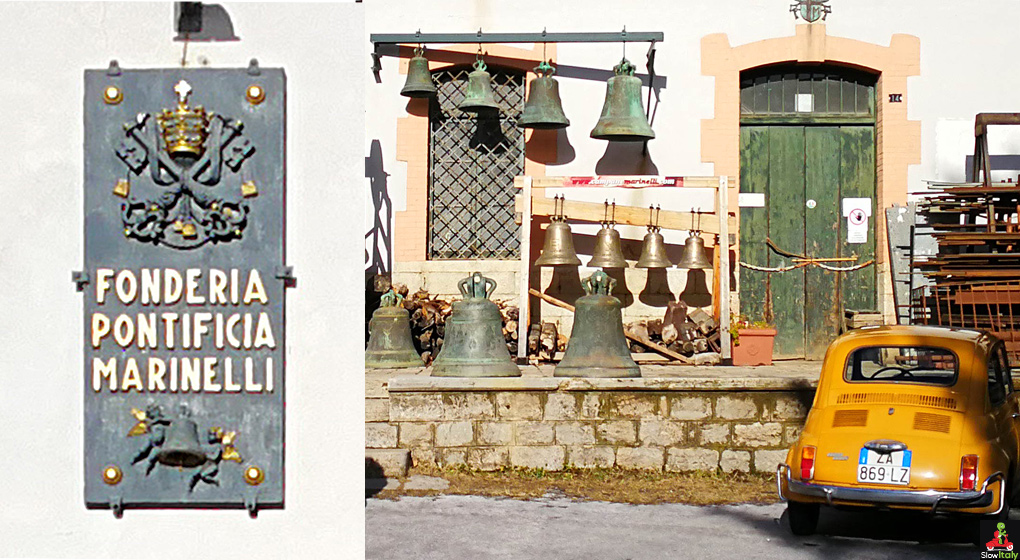

Renowned since the Middle Ages as a prosperous center of various crafts, the city of Agnone is now mostly famous for being the home to the oldest continuously family-owned and run manufacturing company in the world, the Pontifical Bell Foundry Marinelli. It was founded more than 1000 years ago and is still owned and run by descendants of the founding Marinelli family, using the original processes and techniques of its founders. There are a handful of other companies in the world that are even older, but they are either no longer run by the original founding family, or not in the manufacturing sector, or have diversified away from the original family business and/or production techniques. This makes the Bell Foundry of Agnone pretty unique on the world map of oldest companies, and so the next natural question is… why in Agnone?

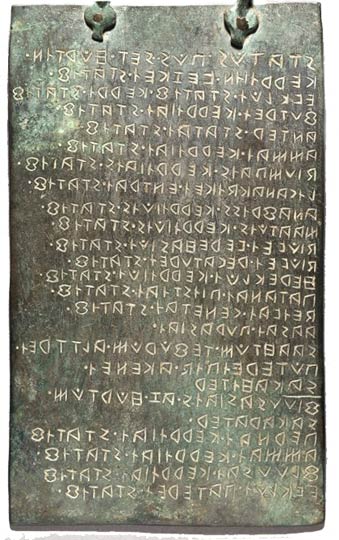

There are a few archaeological, historical and etymological elements that prove that this did not happen here just by chance. From the start, Agnone specialized in the production of sacred bronzes (among which the statues that adorned the Samnite temples). The city’s tradition of smelting and moulding metals is actually more than 2200 years old, as attested by the bronze Tabula Osca (Oscan tablet) dated from ca. 300BC-100BC, which was found near the town of Agnone in 1848.

The Tabula Agnonensis, as it is often referred to, is engraved in the ancient Oscan language of the Samnites, the original people who inhabited the region before Roman conquest.

In 1139, Landolfo Borrello, a descendant of the prominent Counts of Pietrabbondante and mercenary captains of Venice, brought soldiers and craftsmen from the Veneto region to Agnone to develop the local crafts. The Venetian presence is still noticeable in the original borgo of the town, the Ripa, also known as the Borgo Veneziano. The Venetian craftsmen further perfected the local technique of casting metals. As the demand for church bells increased with the expansion of Christianity, bellfounding soon became an important part of the business.

The economic development of Agnone was such that the city was granted the title of città regia (royal city) in 1404, meaning that the city was freed from any feudal domination and placed under direct royal jurisdiction, a denomination reserved to towns of a certain economic or strategic importance. As a reference, out of the circa 1500 population centers of that time only 56 could pride themselves on the title of città regia. The citizens of these royal cities usually also enjoyed a higher statues than the other subjects under baronial or feudal control.

Among the Venetian craftsmen who established themselves in Agnone in the XII century was the Marinelli family. They had already been bronze casters for generations in the Veneto region when they arrived in the city, although it is not exactly known since when. What is sure is that the first bell to bear the name of a Marinelli bell caster was a two-quintal (200kg) bell intended for a Church in the city of Frosinone, casted in 1339 by Nicodemus Marinelli, nicknamed Campanarus.

Throughout the centuries, surviving plagues, fires and wars, the Marinelli family has managed to preserve the arduous and unique method of bell founding developed by their ancestors. To this day, the Marinelli Foundry of Agnone produces bells in much the same way as their forefathers did about 1000 years ago, using clay, earth, wood and metal, without any modern means of heating other than wood furnaces. As Armando Marinelli puts it: “Our production process has remained so close to the Medieval working method that we could still make bells without any use of electricity.”

This invaluable heritage includes not only the tools and craftsmanship techniques, but also the odors, feel and flavors, such as the density of the earth, the feel of the wood, i.e. a complex collection of know how and practices, that can’t be easily codified in writing. These imperceptible, yet fundamental, aspects of the craftsmanship can only be learned on the job, in much the same way as knowing a list of ingredients wouldn’t turn you into a starred chef. No technology or academic curriculum can replace the expertise handed down from generation to generation over a period of more than a millennium!

The ability to choose the right type of wood, for example, is of the utmost importance, as the success of the art of bell making depends for a great deal on the energy-space ratio, in other words the energy efficiency obtained in the, usually, limited space available. The difficulty of the job resides precisely in resolving the challenge of delivering impressive results at very high temperatures on a limited space, which is the reason why wood furnaces, more precisely refractory brick furnaces, heated with oak wood, are preferred over gas-ovens, the latter being considered less efficient.

Traditionally, bells were cast on site in pits dug within or close to the church or the intended place of the bell, as there were no roads on which the bells could be easily transported from the foundry to their place of destination. The furnace was constructed next to the pit in which the bell was built. The metal for the bell was collected on site too, either by recycling the metal stemming from old, broken bells or by using metal objects, tin and copper pots brought by the villagers. It was not uncommon to melt gold wedding rings and other emotionally charged objects into the mix, proving the importance of the village’s bell for the community. The size of the bell was being determined in function of the available metal, after which the itinerant team returned to Agnone, now knowing which tools they had to bring on their next trip (usually the bare minimum as everything had to be transported by carts).

Today, most bells are produced in the foundry, but the entire production process can still take up to three months, with a final two-minutes, decisive moment, the colata (casting) during which the bell is given not only its shape, but also its voice. As bells are made in a single casting, without welding, the final step is the most critical one.

The voice of the bell is obviously central in the process of bell making. In Christianity, the bell was said to represent the “voice of God”, so it was of the utmost importance that the bell’s sound was powerful and pure. Also in other religions bells are believed to directly address spirits or deities and to keep evil spirits away. The earliest metal bells were found in China and are dated to about 2000 BC, but it were Italian monks who resuscitated the ancient craft of bell founding in Europe. Legend has it that it was Paulinus of Nola (c. 354 – 431), Roman poet, bishop of Nola and governor of the Campania region, who introduced the use of bells in church services. It is from the name of the Campania region that the Italian word for bell, campana, takes its etymology. The bells that were produced in the area of Nola were renowned for the quality of their bronze alloy and known as bronzi di Campania (bronzes from Campania), which by eponymy gave rise to the word campana.

Before the advent of the radio, telephone and television, the bell was one of the most important instruments of mass communication. At the time when there were no modern means of communication and transportation, the bell punctuated every aspect of village farming and life. It was a common way to inform or call together a community.

The pattern of striking depended entirely on the type of announcement, whether it was to announce mass, the hours of the day, the angelus, tocsin or knell. The bell was also used to ring the curfew, announcing the closing of the workshops and the town’s gates. Each village developed its own bell language, which allowed inhabitants to differentiate happy moments from sad or solemn events, or an imminent danger, such as an impending invasion, an upcoming storm or burgeoning blaze.

The knell, for example, was used to announce someone’s agony, death or funeral, but the ringing could be different in function of gender, age, or social status. In very small villages it was, therefore, sometimes possible to infer the identity of the person in question only from the way the bell was struck. Tocsin was used to announce something dangerous such as a fire, a war or a riot. The Angelus was rung three times a day to indicate the moments of prayer, but at the same time it was also a way to know when one had to get up and leave to work on the field, when it was time to have a break at noon, or when the farmers who where out on the field had to head back home.

The message transmitted by bell ringing is based on three components: the sound of the bell (the vocal identity of the bell), the tempo, depth, rhythm and number of the strokes, and the number of bells implemented simultaneously or successively. The number of combinations is therefore almost infinite.

It has even been hypothesized that settlements were built “within bell distance” so that friendly neighboring villages could be alerted of an impending invasion or threatening fire by the ringing of one village bell. This also explains why bell towers have become increasingly higher and church bells increasingly larger with the growing size of the settlements. Villagers could even forecast the weather in function of the way in which the sound of the bells in neighboring villages “traveled” through the layers of air, as the sound would vary in function of the air being “thick”, “heavy” or “clear”.

Needless to say that the purity and intensity of the “voice” of the bell is, therefore, of paramount importance. A bell scale was developed by Tommaso Marinelli in the 1700s, which had been elaborated after centuries of practice and is still used today. It defines the exact internal and external profile of the bell, some kind of “golden ratios”, which give the perfect proportions of thickness, weight, circumference, and height in function of the timbre required.

To physically shape the bell, the Marinelli foundry still uses the century-old “soul, false bell and mantle technique“, where the Soul (made of brick and clay) defines the inner shape of the bell and the Mantle (made of layers of clay) the outer shape, while the False bell represents the free space between the two where the molten bronze alloy will be poured, after the False bell has been destroyed.

The alloy used by bell casters is a special bronze alloy, also known as bell metal, consisting of 22% tin and 78% copper, which would be too brittle for engineering applications, but confers the bell its unique sound. Acoustical properties and damping behavior of this type of alloy make it particularly suitable for bell making, as the higher tin content increases the rigidity of the metal, and therefore the resonance. Most people ignore that these heavy and imposing church bells are actually very delicate and breakable. There is a special rite during the fusion, followd by a blessing during which the bell is given the name of a Saint, and a godmother and godfather may be designated.

Before the final and decisive step of the casting, the Soul is covered with the bell’s embossed motives, using the four-millennium-old lost-wax technique, meaning that when the bell’s mold is heated the wax will melt inside, leaving the negative impressions which will become the embossed decorations (friezes, symbols, coats of arms or seals) and written dedications, invocations, mottoes and names (of the patron, caster or person honored), visible on the outside of bells. Each bell is therefore unique and each mold is used only once as it would be the case in a small medieval workshop.

The setbacks the foundry has faced have been numerous through the centuries. After having been requisitioned by the German army for the war effort, a terrible fire destroyed the entire foundry and family house in 1950. The foundry was rebuilt on the outskirts of the town, leading to a “Nuova Agnone” being built around the foundry, which, as a result, became again located at the center of the town’s activity. However, the biggest threat of all is probably the difficulty to find specialized labor today, as it is nearly impossible to achieve this level of proficiency if it is not learned on the job from an early age.

Unfortunately, the art of bell making is a dying craft. Before the last war there were still 70 to 80 traditional bell makers in Europe. Today, they are only a dozen historical foundries left. This is partly due to the lack of motivated descendants, as taking over such a business is similar to a vocation (or should one say a virus?), something that is part of one’s life 24/7. Also, demand is not increasing, as most bell towers have already been equipped and won’t need a new bell for centuries to come.

However, the bell casters’ prowess in the fusion of bronze is such that the artistic applications are infinite. Renaissance artists already entrusted the delicate casting of their bronze sculptures to bell founders’ workshops. The artistic production of the Marinelli Foundry includes: bas-reliefs, statues, busts, medals, and sacred art.

The vocation, dedication, commitment displayed by the Marinelli family to preserve this unique heritage and expertise has been recognized, first, in 1924 when the foundry was bestowed the title of “Pontifical foundry” by Pope Pius XI, meaning that they can use the Papal coat of arms on their bells. In 1954, the President of the Republic handed over the gold medal to the Marinelli family “as an award to the oldest company for their work activities and loyalty at National level.”

Marinelli bells resonate all over the world from the church of the Trinità dei Monti at the top of the Spanish Steps in Rome and the Leaning Tower of Pisa, to New York, Buenos Aires, Montreal, Peking, Macau, Seoul, Mozambique, Sapporo, Tokyo, Hiroshima,…

Some bells were specifically created for commemorative events, such as the five-ton-weighing imposing bell located in the Vatican Gardens that was donated for the Great Jubilee in 2000, the Bell of Marcinelle, fused for the 50th anniversary of the disastrous accident in the Belgian mines, the central bell of the Children’s Bell Tower in California (see photo below), and the Peace bell in Tirana, made by melting about 20,000 gun shells gathered by Albanian children in Shkodra in 1997 at the end of the Albanian Rebellion.

Next to the Marinelli foundry is the Historical Bell Museum, opened in 1997. It contains a large collection of bells of historical value, dating from the year 1000 to today, as well as ancient tools and moulds, and precious manuscripts, among which the 1664 edition of the Tintinnabulis by Girolami Maggi (Hieronymus Magius), the “Bible in the art of Bell making”.

Travel tip:

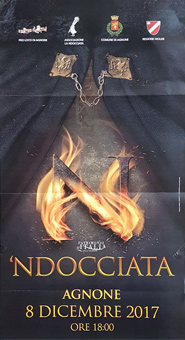

If you’re in Agnone in December, don’t miss one of the most fascinating traditions of the region, the ‘Ndocciata of Agnone, celebrated on December 8th and on Christmas Eve.

It consists of a parade of a large number of hand-fan-shaped, wooden‘ndocce (torches), carried by men dressed in traditional costumes.

Photo credits: all photos © Slow Italy, except Lion in Agnone by Troise Carmine – Washi; Tools and Lost-wax-technique photos © Steve Austin; Bell of the Santuario SS Salvatore by Cesare Andreano, www.facebook.com/cesareandreanoph; Children’s Bell Tower via 4.bp.blogspot.com/bell-tower-yappy-hour/ (author unknown).