Vinci, the birthplace of Leonardo

Situated on the slope of the Montalbano, amid the rolling hills of Tuscany, lies the town of Vinci, the birthplace of Leonardo da Vinci.

It is here, in the heart of the stunning Tuscan countryside, at just 40 km from Florence, that the genius artist and inventor was born on 15 April 1452, the natural child of Florentine notary Ser Piero and a young peasant woman named Caterina. He was raised by his grandparents in a farmhouse located in a frazione of Vinci called Anchiano, surrounded by an amazing landscape made of centuries-old olive trees and the typical bluish misty horizons as seen in many of his paintings.

It is quite touching to see that, throughout his life, the world famous genius kept a close relationship with his home territory, the scenery that inspired his works. Indeed, the background hues of the Mona Lisa, one of the most famous portraits of all time, was clearly inspired by the landscapes of his early childhood, even though the bridge visible in the backgrod is believed to be the Ponte Gobbo from Bobbio in Emilia Romagna.

It is quite touching to see that, throughout his life, the world famous genius kept a close relationship with his home territory, the scenery that inspired his works. Indeed, the background hues of the Mona Lisa, one of the most famous portraits of all time, was clearly inspired by the landscapes of his early childhood, even though the bridge visible in the backgrod is believed to be the Ponte Gobbo from Bobbio in Emilia Romagna.

In the chapter on Perspective of Color and Aerial Perspective of his Notebooks, da Vinci recommended the blue horizon and gave as a reason that in reality horizons are blue.

Standing in front of the farm house where Leonardo spent his childhood, overlooking the amazing scenery all around, it is easy to understand why this celestial feature was given so much importance in his paintings.

Leonardo da Vinci was the epitome of a “Renaissance man”, a person who excelled at several fields in science and the arts, a polymath of fervent curiosity, coupled with a visionary and vivid imagination.

Polymaths had a comprehensive approach to education that reflected the ideals of the humanists of the time.

According to the Renaissance ideal, one was expected to be versed in science, technology and philosophy, speak several languages, play a musical instrument and write poetry. This is in sharp contrast to our modern day assumption that excellence or expertise can only result from focusing on a single specific topic and where certain alliances between subjects are not as easily “tolerated”, especially not within one and the same person.

During the Renaissance, excellence in any of these areas was not supposed to take attention away from the pursuit of the other fields, but rather served to increase competence in complementary areas, in order to provide a greater understanding of oneself and the world.

The idea was certainly not to have a superficial understanding of many topics, but rather to have a profound knowledge in each of the fields, which allowed to “connect the dots”. Many notable polymaths lived during the Renaissance period, hence the term. Galileo, for example, painted and played the lute alongside his mastery of science and philosophy.

As for Leonardo, he was a brilliant scientist, inventor, painter, sculptor, architect, mathematician, engineer, cartographer, writer, poet and musician. Even though he is renowned primarily as a painter, his expertise in each of the other fields contributed to his unique skills as a universal genius.

Leonardo thought that the eyes are human kind’s most important organ and sight the most important of our five senses. Therefore, he believed in the amassing of direct knowledge through observation. Saper vedere (“knowing how to see”) became one of the central themes of his studies.

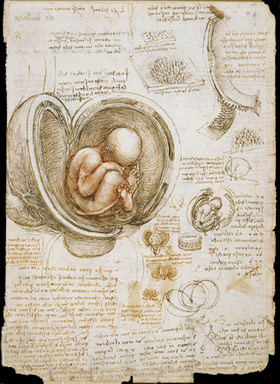

His creativity reached out in every realm in which vision and graphic representation go hand in hand: painting, sculpting, architecture and engineering. But, he went much further than that. His unusual powers of observation and mastery of the art of drawing allowed him to sketch his findings when dissecting human and animal bodies.

Combining several of his unique skills in an alliance of art and science, he became one of the first artists to make detailed anatomical drawings from his own dissections, at a time when dissection of the human body was still very rare. His drawings of fetus in utero, sex organs and other anatomical features are some of the first recorded in human history. Reversely, his dissections also allowed him to more accurately depict movements and gestures in his paintings.

Art and science intersected also perfectly in his sketch of the “Vitruvian Man,” which depicts a man in two superimposed positions with his arms and legs apart, inscribed in both a square and a circle. The drawing and the accompanying text (based on the work of the Roman architect Vitruvius) are sometimes viewed as the Canon of Proportions. The Canon of Proportions is a type of ideal proportions in which the human body was the principal source of proportions among the Classical orders of architecture, a kind of intersection between geometry and ideal human proportions. According to this ideal the human body should be eight heads high. A real-life representation of the Vitruvian Man, by Mario Ceroli, can be seen right behind the tower of the Castle of Vinci, where it is strategically placed against the panorama surrounding it.

However, da Vinci acknowledged the risk of being stuck in one’s own perceptual position, and he indicated several ways to shift perspective, both literally and mentally.

A striking example is the painting Annunciation (1472-1473), which is generally considered a work denoting the immaturity of the artist due to so-called errors in perspective and strange deformations from a spatial point of view. It is in fact a quintessence of his research in optics. When you move to the right side of the painting, you will see that the proportions of the palazzo change and the whole picture becomes more realistic.

The reading-desk is now also further back and much closer to Mary; her right arm is shorter and the posture more natural; and finally, Gabriel’s stance is more compact, as is appropriate for a kneeling figure in the act of greeting Mary.

In addition to his anatomical investigations and his research in optics, da Vinci studied aeronautics, hydraulics, mathematics, physics, geology, botany and zoology. He sketched his observations on loose sheets of papers that were arranged in dozens of notebooks around four comprehensive themes: painting, architecture, mechanics and human anatomy.

Despite his groundbreaking discoveries in anatomy, civil engineering, optics, and hydrodynamics, he did not publish his findings, which explains why they had no direct influence on later science.

Ahead of his time, da Vinci seemed to prophesize the future with his sketches of machines resembling an airplane, bicycle and helicopter, but his sketches were mainly theoretical, rarely experimental, as the technology was lacking at that time to develop his plans, which, if anything, is an additional proof of his unusual ingenuity. His sketch of the ancestor of an airplane was based on the physiology of the bat, again demonstrating the alliance of his skills in various fields, in this case biology and engineering. A number of Leonardo’s most interesting inventions are now on display as working models at the Museum of Vinci.

While Leonardo is widely recognized as one of the most diversely talented individuals to have ever lived, it goes relatively unnoticed that he did in fact receive little formal education beyond basic reading, writing and mathematics instruction. His artistic talents, however, were evident from an early age. By the age of 14, da Vinci began a lengthy apprenticeship with the famous Florentine artist Andrea del Verrocchio. While in Florence, he learned a wide variety of technical skills including carpentry, metalworking, leather arts, painting and sculpting. His earliest known dated work is a pen-and-ink drawing of an Arno landscape, sketched in 1473.

Barely fifteen of his paintings have survived, but he probably never painted more than two dozen. One reason is that his interests were so varied that he was too absorbed to be a prolific painter. Nevertheless, these few works, together with his thoughts on the nature of painting, form a contribution to later generations of artists rivaled only by that of his contemporary, Michelangelo. Among his works, the Mona Lisa and The Last Supper are both the most famous and most reproduced paintings of all time.

It was under the patronage of Ludovico Sforza, who ruled Milan as its regent, that da Vinci painted The Last Supper on the back wall of the dining hall inside the monastery of Milan’s Santa Maria delle Grazie. Ludovico brought da Vinci to Milan for a tenure that would last 17 years.

The Mona Lisa, instead, was a privately commissioned work. Much of the painting’s allure is due to the enigmatic smile of the woman in the half-portrait, which derives from da Vinci’s sfumato technique. The mystery surrounding the identity of the subject is also a source of endless fascination. The most accepted theory is that the painting’s model was Lisa Gherardini del Giocondo, the wife of a wealthy Florentine silk merchant. The painting’s original Italian name, “La Gioconda”, supports this theory. Some art historians, however, believe that the portrait is androgynous (half male, half female) and that it was either partly a self-portrait or that Da Vinci’s apprentice and lover Gian Giocomo Caprotti sat as a model for the painting. Even though it was a privately commissioned work it was never delivered as Da Vinci considered it forever a work in progress, so there isn’t any delivery destination that could confirm the identity of the model.

During his stay in Milan da Vinci also worked as a military engineer for the regent, sketching war machines such as a war chariot with scythe blades mounted on the sides, an armored tank. The Duke of Milan also tasked him with designing a dome for Milan’s cathedral.

In the beginning of the 1500s, he briefly worked as a military engineer for Cesare Borgia, the illegitimate son of Pope Alexander VI and commander of the papal army. Together with the politician and diplomat Niccolò Machiavelli, he developed an innovative weapon of war: the diversion of the Arno River away from rival Pisa in order to deny its wartime enemy access to the sea.

Towards the end of his life Da Vinci moved to Rome, then to France, where, lacking large commissions, he devoted most of his time to mathematical studies and scientific exploration.

If you are in Florence, the picturesque village of Vinci with its evocative medieval alleys and panoramic views is certainly worth a day trip. The town has paid a beautiful tribute to its most famous son, expressing the past-future relationship between the Renaissance genius and his futuristic works, in its squares, streets and the Leonardo Museum (Museo Leonardiano). The artist’s sketches, inventions and handwritten notes have been wonderfully brought to life in the real-life abstract sculptures that adorn the town and in the wooden models exhibited in the museums, many of which are supported by digital animations and interactive software.

The Leonardo Museum consists of two parts, one housed in the XIIIth century Castle of the Guidi Counts, restored in 1952 to create the museum, and one inside the Palazzina Uzielli (where the ticket booth is located). The two buildings together house one of the broadest and most original collections devoted to Da Vinci the engineer, architect and scientist, and to the history of Renaissance technology in general.

The visit of the Leonardo museum starts on the first floor of Palazzo Uzielli. The various sections are dedicated to applied textile technology, construction machinery and mechanical watches and a separate section explaining Leonardo’s calculations for the construction of Brunelleschi’s dome in Florence. From there the visit continues in the Guidi Castle, dedicated to Leonardo’s war machines, architecture and engineering.

In the flight section you will find the famous beating wing, the designs of automatic mechanisms, such as those for operating bells. Further rooms include the room of the bicycle, optics and water and the studies dedicated to river transportation. From the tower of the castle you can enjoy spectacular views of the surrounding area.

Copies of all Leonardo’s manuscripts and sketches are kept in the Leonardo Library. The Library (Biblioteca Leonardiana) also contains over 7,000 monographies on Leonardo Da Vinci.

Next to the museum is the Church of Santa Croce, where the original 15th century baptismal font where Da Vinci was baptized is still visible. The church also houses a sculptural cycle, inspired by Da Vinci, by one of the most famous contemporary Italian sculptors Cecco Buonanotte.

In Piazza Guidi the artist Mimmo Paladino has reinterpreted Leonardo’s geometry in his own unique artistic language, creating an original urban space which marks the entrance to the Museum. The sculptures with their geometric and abstract shapes were inspired by the polyhedron, symbol of the Renaissance, composing a symbolic dialogue between the medieval heart of Vinci and the contemporary effect of the glass and silver laminate sculptures.

On Piazza della Libertà stands the bronze Horse statue by the Japanese-American sculptor Nina Akamu, taking inspiration from Leonardo’s project for an equestrian monument to Francesco Sforza which was never finished. The artist was commissioned by Ludovico Sforza to sculpt a 16-foot-tall bronze equestrian statue, meant to be the largest equestrian statue in the world, as a tribute to his father and founder of the family dynasty, Francesco Sforza.

The sculpture exhibited in Vinci is actually a smaller scale version of the Cavallo di Leonardo by the same artist Nina Akamu, made in two castings, of which one is exhibited in Milan and one, The American Horse, stands in the Frederik Meijer Gardens in Grand Rapids, Michigan.

As we mentioned at the beginning of the article, there is also the wooden sculpture The Man of Vinci by Mario Ceroli, a real-life representation of the Vitruvian man, right behind the tower of the Castle.

Da Vinci’s birth house, instead, is located at 3km from the center, the frazione Anchiano of Vinci. It is worth visiting, if only for the breathtaking ride through the amazing scenery on the road bordered with century-old olive trees. You can also walk up following the picturesque Strada Verde (Green Road) on foot for about 30 minutes (CAI path n.14). The surrounding nature and breathtaking viewpoints are those that inspired the young da Vinci!

Directions:

From Florence follow the road to Empoli, then drive along the Arno until the Zona Industriale and follow the SP13 towards Vinci.

When to visit:

A framework of celebrations are usually organized between mid-April and the end of June (corresponding approximately to the birth and death-month of Da Vinci).

During the second weekend of April, a cultural gathering called Lettura Vinciana, which is a critical review of one of the works of Leonardo with Da Vinci readings, is being held. Each year, it is curated by a different international exponent of the world of culture or world expert on Leonardo.

The ‘Unicorn Festival’ (Festa Unicorno) in Vinci, is however, the most intense and original event, which has taken place every year since 2004. For three consecutive days during the second half of July a fantasy world of elves, goblins, knights of the Hobbit world, Adventure Comics characters invades the streets of Vinci creating a huge party of colors, costumes and thematic music concerts.

Last but not least is the Volo of Cecco Santi, which takes place during the last week of July. It is a rite for the harvest of Vinci’s fields and consists of a historical parade in medieval dress on the streets of Vinci, the flight of Cecco Santi puppet from the Castle and one breath-taking fireworks display. According to the legend, Cecco Santi di Vinci was a guard knight of fortune who, for the love of a noblewoman, became corrupted by the opposing attackers to encourage their entry into Vinci. He was discovered and sentenced to be thrown from the tower of the Castle of the Guidi Counts. Cecco asked to drink, as a last wish, a good wine glass of Vinci, a miraculous wine because the traitor and womanizer rider was able to fly and had thus saved his life. The story of Cecco is known throughout Tuscany and should be seen in the 14th century and the background are the struggles between Guelphs and Ghibellines which plagued Florence and Tuscany.

Photo credtis: all photos © Slow Italy, except when otherwise stated.